In Brief

He’s knowledgable, sensible, passionate, lucid, unpretentious. But the simplest reason Time Magazine’s Robert Hughes is possibly the best art critic writing today is that he’s always interesting. Even when you disagree with him, it’s impossible not to enjoy doing so.

You have to be an intellectual to believe such nonsense. No ordinary man could be such a fool. George Orwell was talking politics when he coined this aphorism — one of The Best Things Anybody Ever Said — but he might just as well have been referring to the art world in the 20th century and beyond. In such an age, Robert Hughes is a refreshingly sane voice.

Hughes was born in Sydney, Australia in 1938. He studied arts and architecture at Sydney University, during which time he made a name for himself within the Sydney “Push” — a progressive group of artists, writers, intellectuals and drinkers. Among the group were two other blazingly witty and incisive cultural observers: Germaine Greer and Clive James. Incredibly, Hughes was commissioned to write a history of Australian painting while an undergraduate and dropped out of university.

He left Australia for Britain in the early 1960’s, writing for such publications as the Spectator, the Telegraph, the Times and the Observer, before landing the position of art critic for Time Magazine in 1970.

Important books he has written include The Shock of the New (1981), The Fatal Shore (1987), Culture of Complaint (1993) and American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America (1997).

Hughes had established an unassailable position as the world’s most famous and most influential art critic, when things recently started to go wrong for him. He had a nervous breakdown in 1997. While in Australia in 1999 to film the documentary Beyond the Fatal Shore, he was in a head-on collision and nearly died. He was accused of causing the accident (of which he has no recollection) and charged with dangerous driving. Then when the show ultimately aired, Hughes was accused of showing a negative and outdated view of Australia.

sourced http://www.artcyclopedia.com/robert_hughes.html

Some notable quotes from Hughes

- The auction room, as anyone knows, is an excellent medium for sustaining fictional price levels, because the public imagines that auction prices are necessarily real prices.

- Drawing brings us into a different, a deeper and more fully experienced relation to the object.

- Most of the time they buy what other people buy. They move in great schools, like bluefish, all identical. There is safety in numbers. If one wants Schnabel, they all want Schnabel, if one buys a Keith Haring, two hundred Keith Harings will be sold.

- Drawing never dies, it holds on by the skin of its teeth, because the hunger it satisfies.. the desire for an active, investigative, manually vivid relation with the things we see and yearn to know about.. is apparently immortal.

- Art prices are determined by the meeting of real or induced scarcity with pure, irrational desire, and nothing is more manipulable than desire.

- The idea that money, patronage and trade automatically corrupts the wells of imagination is a pious fiction, believed by some Utopian lefties and a few people of genius such as (William) Blake but flatly contradicted by history itself.

- With its hacked contours, staring interrogatory eyes, and general feeling of instability, Les Demoiselles is still a disturbing painting after three quarters of a century, a refutation of the idea that the surprise of art, like the surprise of fashion, must necessarily wear off. No painting ever looked more convulsive.

- The museum has very largely supplanted the church as the emblematic focus of the American city.

- On the whole, money does artists much more good than harm. The idea that one benefits from cold water, crusts and debt collectors is now almost extinct, like belief in the reformatory power of flogging.

- A fair price is the highest one a collector can be induced to pay.

- I have always tended to take art contextually. If I have any merits as a critic, they have to do with my ability as a storyteller.. and above all I wanted to tell a story.

- I don’t like the idea of art being a pseudo-religion. I love genuinely visionary, mystical art.

- I think the biggest single difference between Australians and Americans is that you were founded as a religious experiment, and we were founded as a jail.

- Duchamp is a hugely overrated artist. Duchamp was the first artist who really became a great master at the art of curating his own reputation. Other artists had done it before, but Duchamp was the first modernist artist to do it.

- I am often viewed as a “conservative” critic. On the other hand, what does “conservative” and what does “radical” mean in today’s context? As far as I can make up, when an artist says that I am conservative, it means that I haven’t praised him recently.

Hughes on Damien Hirst.

“Damien Hirst’s works are “absurd” and “tacky commodities”, according to Robert Hughes, a prominent Australian art critic.

The critic said commercial pieces with large price tags mean “art as spectacle loses its meaning” and identified the British artist’s work as a cause of that loss. Hughes says it is “a little miracle” Hirst’s 35ft statue Virgin Mother, could be worth £5 million and yet be made by someone “with so little facility.”

He calls Hirst’s formaldehyde tiger shark, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a “tacky commodity”, and “the world’s most over-rated marine organism”, despite collector Charles Saatchi selling it for close to £7 million in 2004.

His criticism comes amid claims Hirst is now so rich he is a dollar billionaire, and if his empire continues at the rate it is going, he will soon be worth more than Sotheby’s, the auction house.

Hughes, 70, is famous for his 1980 BBC series The Shock of the New, which made the theories behind modernism in art accessible to a wider audience.

The latest attack was made in a Channel 4 documentary about art and money called The Mona Lisa Curse, to be shown on September 21, which details Hughes’s observations over 50 years as a New York-based art reviewer.

He says works of art now operate like film stars, starting in 1962 when Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa left The Louvre in Paris to go on display in New York, the long queues turning the masterpiece into a mere spectacle.

It is not the first time Hughes has made public his contempt for Hirst’s art. Making a speech four years ago at the Royal Academy of Art’s annual dinner, he said: “A string of brush marks on a lace collar in a Velazquez can be as radical as a shark that an Australian caught for a couple of Englishmen some years ago and is now murkily disintegrating in its tank on the other side of the Thames.”

sourced at Telegraph.co.uk

“By now, with the enormous hype that has been spun around it, there probably isn’t an earthworm between John O’Groats and Land’s End that hasn’t heard about the auction of Damien Hirst’s work at Sotheby’s on Monday and Tuesday – the special character of the event being that the artist is offering the work directly for sale, not through a dealer. This, of course, is persiflage. Christie’s and Sotheby’s are now scarcely distinguishable from private dealers anyway: they in effect manage and represent living artists, and the Hirst auction is merely another step in cutting gallery dealers out of the loop.

If there is anything special about this event, it lies in the extreme disproportion between Hirst’s expected prices and his actual talent. Hirst is basically a pirate, and his skill is shown by the way in which he has managed to bluff so many art-related people, from museum personnel such as Tate’s Nicholas Serota to billionaires in the New York real-estate trade, into giving credence to his originality and the importance of his “ideas”. This skill at manipulation is his real success as an artist. He has manoeuvred himself into the sweet spot where wannabe collectors, no matter how dumb (indeed, the dumber the better), feel somehow ignorable without a Hirst or two.

Actually, the presence of a Hirst in a collection is a sure sign of dullness of taste. What serious person could want those collages of dead butterflies, which are nothing more than replays of Victorian decor? What is there to those empty spin paintings, enlarged versions of the pseudo-art made in funfairs? Who can look for long at his silly sub-Bridget Riley spot paintings, or at the pointless imitations of drug bottles on pharmacy shelves? No wonder so many business big-shots go for Hirst: his work is both simple-minded and sensationalist, just the ticket for newbie collectors who are, to put it mildly, connoisseurship-challenged and resonance-free. Where you see Hirsts you will also see Jeff Koons’s balloons, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s stoned scribbles, Richard Prince’s feeble jokes and pin-ups of nurses and, inevitably, scads of really bad, really late Warhols. Such works of art are bound to hang out together, a uniform message from our fin-de-siècle decadence.

Hirst’s fatuous religious references don’t hurt either. “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever”, the sale is titled. One might as well be in Forest Lawn, contemplating a loved one – which, in effect, Hirst’s embalmed dumb friends are, bisected though they may be. Consider the Golden Calf in this auction, pickled, with a gold disc on its head and its hoofs made of real gold. For these bozos, gold is religion, Volpone-style. “Good morning to the day; and next, my gold! Open the shrine, that I may see my saint!”

His far-famed shark with its pretentious title, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, is “nature” for those who have no conception of nature, in whose life nature plays no real part except as a shallow emblem, a still from Jaws. It might have had a little more point if Hirst had caught it himself. But of course he didn’t and couldn’t; the job was done by a pro fisherman in Australia, and paid for by Charles Saatchi, that untiring patron of the briefly new.

The publicity over the shark created the illusion that danger had somehow been confronted by Hirst, and come swimming into the gallery, gnashing its incisors. Having caught a few large sharks myself off Sydney, Montauk and elsewhere, and seen quite a few more over a lifetime of recreational fishing, I am underwhelmed by the blither and rubbish churned out by critics, publicists and other art-world denizens about Hirst’s fish and the existential risks it allegedly symbolises.

One might as well get excited about seeing a dead halibut on a slab in Harrods food hall. Living sharks are among the most beautiful creatures in the world, but the idea that the American hedge fund broker Steve Cohen, out of a hypnotised form of culture-snobbery, would pay an alleged $12m for a third of a tonne of shark, far gone in decay, is so risible that it beggars the imagination. As for the implied danger, it is worth remembering that the number of people recorded as killed by sharks worldwide in 2007 was exactly one. By comparison, a housefly is a ravening murderous beast. Maybe Hirst should pickle one, and throw in a magnifying glass or two.

Of course, $12m would be nothing to Cohen, but the thought of paying that price for a rotten fish is an outright obscenity. And there are plenty more where it came from. For future customers, Hirst has a number of smaller sharks waiting in large refrigerators, and one of them is currently on show in its tank of formalin in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Inert, wretched and wrinkled, and already leaking the telltale juices of its decay, it is a dismal trophy of – what? Nothing beyond the fatuity of art-world greed. The Met should be ashamed. If this is the way America’s greatest museum brings itself into line with late modernist decadence, then heaven help it, for the god Neptune will not.

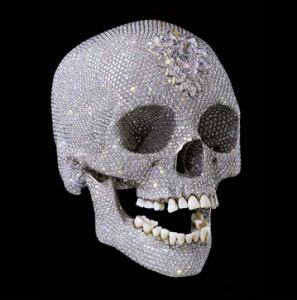

The now famous diamond-encrusted skull, lately unveiled to a gawping art world amid deluges of hype, is a letdown unless you believe the unverifiable claims about its cash value, and are mesmerized by mere bling of rather secondary quality; as a spectacle of transformation and terror, the sugar skulls sold on any Mexican street corner on the Day of the Dead are 10 times as vivid and, as a bonus, raise real issues about death and its relation to religious belief in a way that is genuinely democratic, not just a vicarious spectacle for money groupies such as Hirst and his admirers.

It certainly suggests where Hirst’s own cranium is that his latest trick with the skull is to show photos of the thing in London’s White Cube gallery, just ordinary photo reproductions made into 100cm x 75cm silkscreen prints and then sprinkled (yay, Tinkerbell, go for it!) with diamond dust, and to charge an outrageous $10,000 each for them. The edition size is 250. You do the maths. But, given the tastes of the collectoriat, he may well get away with this – in the short run. Even if his auction makes the expected tonne of money, it will bid fair to be one of the less interesting cultural events of 2008.”

sourced at http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/sep/13/damienhirst.art

Robert Hughes: A refreshingly frank comment on the art market

By Paul Bond

14 October 2008

On September 16, even as Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch were collapsing, Damien Hirst was setting a new record for sales at auction by an individual artist. His private auction at Sotheby’s netted him $197.8 million.

The staggering sums accrued here, particularly against the backdrop of such a massive financial crisis, indicate a new stage in the commodification of artwork. It is to the credit of the critic Robert Hughes, therefore, that his Channel 4 programme, “The Mona Lisa Curse,” sought to explore and lay bare the ways in which the market stifles and dominates artistic endeavour.

In the programme, one of three one-off shows by different filmmakers on the broad theme of “Art and Money,” Hughes looked at historical changes in exhibiting and selling art over the last half century. He was unafraid to give his opinion of just how bad much of this art is and how it is marketed and bought for commercial rather than aesthetic reasons. In the other programmes, Marcel Theroux looked at the bulk purchase of artworks by a new layer of Russian oligarchs, and Ekow Eshun examined the growth in purchases of Australian Aboriginal artworks.

“The Mona Lisa Curse” was in many ways a deeply personal film. A trip to Florence in the aftermath of the floods of 1966 pushed Hughes towards an appreciation of the significance and cultural value of art, and led to him becoming a critic. In 1970, he was offered the post of art critic at Time magazine. He moved to New York, where he was close to a number of artists, including Robert Rauschenberg. The film saw him revisiting many of the places and individuals he had known then.

However, even if the film had a personal tone–particularly over his sense of loss at the death of his friend Rauschenberg–Hughes rarely allowed this to lure him into sentimentality. Much of the hostility towards the show has accused Hughes of adopting a reactionary nostalgia about how much better things used to be. For the most part, he used his personal experiences to illustrate his general thesis. Whatever disagreements one might have with him, he is a serious critic. His argument has some weight.

Hughes dates the beginning of the present malaise within art and art exhibition to 1963, when the Louvre arranged to show the Mona Lisa in Paris. Hughes identifies a number of trends emerging from this moment. For the first time, people queued round the block “not to look at [the Mona Lisa], but to say that they’d seen it.” Meaning within the artwork became secondary to it as spectacle. Every generation started looking for “its” Mona Lisa, and elevating works of art to celebrity status.

It was also the beginning of the global branding of galleries, which has seen the major museums opening franchised branches around the world. Later in the programme, Hughes looked at the proposed Abu Dhabi branch of the Louvre. According to a New York Times article last year, entitled “The Louvre’s Art: Priceless. The Louvre’s Name: Expensive,” this deal is costing $520 million for the use of the name, with a further $747 million going to the French government for art loans, exhibitions, and management advice.

The programme was devastating in demonstrating the way in which the major galleries have gone along with the frenzied racketeering of the art market. Hughes charted the development of the dealers and brokers. Through the 1960s, the New York taxi entrepreneur Robert Scull had built up a large collection of pop art, buying works cheaply direct from the artists. In 1973, he sold 50 works at auction for $2,242,900. Watching footage of Rauschenberg arguing with Scull after the auction, the sense of betrayal is palpable. Rauschenberg shouted, “I’ve been working my ass off just for you to make that profit!”

Scull told Rauschenberg that although he had not benefited from the sharp rise in prices at this auction, the general trend would be good for the artist as it would raise his prices overall. This was the art market breaking cover. As Hughes drew out, it was the collector emerging as the determining figure in that market.

In a contemporary documentary on that auction, Scull declared that “Acquisition is…probably the most exciting kind of involvement” in art. In practice, this has meant an increasing importance of collectors, who bulk-buy art by individual artists as a means of pushing up prices. “The market is manipulated by collectors who decide to bid up the work of an artist [whose work they already own],” explains Hughes. “So when artist X comes up…the collectors all bid it up, so that they can then multiply the value of their existing holdings in artist X by the value of the inflated sale.”

This has two knock-on effects for public viewing of art. Galleries, which have been the sole access to such works for ordinary people, are priced out of the market by a layer of financial oligarchs. “Instead of being the common property of humankind…art becomes the particular property of somebody who can afford it. And when you have some Russian squillionaire who started buying art three minutes ago but has the GNP of Georgia in his pocket, how can museums compete? They can’t–which causes great social harm.”

The other effect, which Hughes outlined with withering contempt, is that the galleries collude in this process. New wings are funded by and named after private benefactors. Galleries acquire works that drive up the market value of those artists. Hughes has elsewhere been particularly critical of museum curators who have given credence to Damien Hirst’s “originality and the importance of his ‘ideas.’ ”

He has criticised both London’s Tate and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art for playing along with this. Hedge fund broker Steve Cohen bought Hirst’s original shark in formaldehyde, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, for $12 million. Hirst has a number of smaller sharks awaiting similar treatment for future customers. The original maintains its price and guarantees the price of its successors, even as it wrinkles and decays, to large extent because of its exposure in galleries like the Met. Hughes reserves much of his scorn for the exhibition of this work (“The Met should be ashamed”), which he describes as “a dismal trophy of…[n]othing beyond the fatuity of art-world greed.”

As his interviews with collectors and advisors showed, this process has led to a direct assault on the idea that art should have any significance or meaning. His interview with Alberto Mugrabi, one of the leading collectors of Warhol, was particularly revealing. Hughes has written thoughtfully about some of Warhol’s early work, but he is dismissive of most of his oeuvre and seemed about to choke with surprise at hearing the artist described as a “visionary.”

Mugrabi is one of the clearest examples of what Hughes is describing: having bid unsuccessfully for a Warhol self-portrait two years ago, he told press, “I’m only helping my collection. If I don’t get it, I’m keeping the market healthy.” His lawyer said Mugrabi’s father Jose had been among the first to see “not only Warhol’s importance as an artist, but the economic upside of collecting him.” These comments were made last year when the Mugrabis were negotiating the sale of some pictures to form the basis of a dedicated Warhol museum somewhere in the Middle East. John Martin of the Gulf Art Fair called Warhol the “obvious choice” for such a museum. “As a modern brand name, no one is bigger than Warhol.”

When Hirst announced his direct auction, he made a big play that this marked the liberation of the artist from the manipulation of gallery-owners and dealers. Even before the auction took place, Hughes was scathing about such claims, noting that the auction houses are “now scarcely distinguishable from private dealers.” As details emerged afterwards, it became ever clearer that the Sotheby’s auction was yet another example of the process outlined by Hughes. Hirst has grown fabulously rich, if that is somehow supposed to signify the “liberation” of the artist. But even he is dependent to a great extent on the bidding of his dealers, Jay Jopling and Larry Gagosian, who bought some works and bid up some of the pieces less likely to do well. Hughes has called the art world the biggest unregulated market outside of illicit drugs.

It was, it must be said, difficult to suppress a cheer at the thoroughness of Hughes’s demolition job. His acuity made him a difficult act to follow: the second programme in the series saw Marcel Theroux prostrate before all the thinking Hughes was condemning, repeatedly capable only of asking how much a painting was worth. The trend has been to look at the price tag, and commentators are left mute before the artworks.

Unsurprisingly, Hughes was excoriated by some for his exposé. One of the most dismissive responses came from Germaine Greer. Writing in the Guardian, Greer accused Hughes of “not getting” Hirst. Embracing everything Hughes had fought against in his programme, she elevated the banality of Hirst’s work to the level of a artistic statement in itself and hailed his marketing genius as an act of creation: “Damien Hirst is a brand, because the art form of the 21st century is marketing. To develop so strong a brand on so conspicuously threadbare a rationale is hugely creative–revolutionary even.”

She dismissed Hughes with a glib, “Bob dear, the Sotheby’s auction was the work.”

At bottom, Greer was attacking Hughes’s view that art should have some substance and meaning (“Hughes still believes that great art can be guaranteed to survive the ravages of time, because of its intrinsic merit. Hirst knows better”). Talking of Rauschenberg, Hughes said his work made us “experience things more clearly.” He dismissed the notion that the marketing of vacuous artworks itself constituted a work of art. There is, he said correctly, no critique of decadence in such work, which is clearly aimed at a layer of the wealthy who want something that claims to be challenging without actually being so. It is decadence. As Hughes has put it, “No wonder so many business big-shots go for Hirst: his work is both simple-minded and sensationalist.”

There is, too, in Greer’s attack, an attempt to reduce this to a dispute between Hughes and Hirst. As Hughes makes clear, Hirst is simply one of the more successful of a string of artists producing such inferior work. Nurtured by collectors/entrepreneurs (in Hirst’s case Charles Saatchi) as part of their investment portfolio, these figures turn away from artistic explorations. Instead, they have their workshops turning out the requisite number of pieces, of recognisable design, devoid of artistic merit. Hughes’s film makes the valuable point that volume production is an essential function of any artist that might be considered to be “collectable.” Producing art on what is effectively an industrial scale-particularly in the case of Warhol and Hirst-in itself must lead to a churning out of empty pieces. Hughes points the finger at these artists: “[T]he presence of a Hirst…is a sure sign of dullness of taste…. Where you see Hirsts you will also see Jeff Koons’s balloons, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s stoned scribbles, Richard Prince’s feeble jokes and pin-ups of nurses and, inevitably, scads of really bad, really late Warhols.”

He has described such works as a “uniform message from our fin-de-siècle decadence.”

What made this programme such a pleasure was that Hughes continues to believe that art, to qualify as such, must have some content. Even where one might reach different conclusions about an individual artist, there is something heroic in his insistence that art should say something profound about our lives. As he wrote four years ago “Not everything of value is self-evident and there is no reason in the world why art should be.”

He is unafraid to expose the market pressures to churn out vacuous and self-satisfied work. If, at times, he sounds a Cassandra note, fearing that the tide has overrun him, he is still bold enough to call such work what it is. In an atmosphere where wealth and patronage demand conformity and a suspension of critical faculties, his readiness to proclaim the emperor naked is deserving of much praise.

sourced at http://www.wsws.org/articles/2008/oct2008/hugh-o14.shtml

Here is another take from a different angle

The Mona Lisa Curse

“Last night I watched The Mona Lisa Curse, written and presented by Robert Hughes, an Australian art critic residing in New York who’s been er criticising for years. It was really good, an hour and a half with a lot of filler and mood music, but otherwise v interesting. I just wanted to record what he said, somewhere, otherwise I’ll forget. And since I have this spanking new blog system to try out, I may as well have a go here. I can always delete it later if I get too weirded out.

Essential point of the programme was that the value of a piece of art has come to be seen in monetary terms. Hughes began and ended the programme with Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull For The Love of God (see below), supposedly sold for £50 million, making it the most expensive piece of art ever made. Amusing excerpt from Wikipedia:

‘Hirst claims that the piece was sold on 30 August 2007, for £50 million, to an anonymous consortium[8]. Christina Ruiz, editor of The Art Newspaper, claims that Hirst had failed to find a buyer and had been trying to offload the skull for £38 million[9]. Immediately after these allegations were made, Hirst claimed he had sold it for the full asking price, in cash, leaving no paper trail.

Harry Levy, vice chairman of the London Diamond Bourse and Club, said “I would estimate the true worth of the skull as somewhere between £7 million and £10 million.”[9] Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs would expect £8.5 million in VAT payments, if Hirst really did receive £50 million.[9] David Lee, editor of The Jackdaw, commented “Everyone in the art world knows Hirst hasn’t sold the skull. It’s clearly just an elaborate ruse to drum up publicity and rewrite the book value of all his other work.”[9]‘

Am I allowed to just lift stuff? Anyway Hughes claimed this piece was the ultimate demonstration of how art culture has changed. Rather than mirroring society’s decadence, he says it is decadence in itself. The rest of the documentary involved conversations with various leading members of NYC’s art elite, cut with shots of Hughes staring glumly out of various windows as he narrated despairingly over the top. Among these were the people whose job it is to choose art for wealthy investors (they were awful), and a billionaire who with his dad owned 800 Warhols. Hughes visited him and challenged him to explain what he liked about Warhol, and Richard Prince who he also collected. Hughes felt Warhol did some good paintings early in his career but ended up a dull businessman who had become part of the machine (he also knew him). He spoke to another older guy who had a v important job choosing works of art for museums around the world. He too thought Warhol was massively overrated compared to other important artists of his day. Robert Rauschenberg was a friend of Hughes’ and very highly thought of, thought to be far more influential in the modern art movement; to my shame I’d never heard of him..! He also went back to the turning point, where buying art became an investment. A fellow called Robert Skull started buying up artists’ work back in the 50s and sold it on at exhibition for a huge mark-up. Rauschenberg famously gatecrashed the big exhibition that included his work and attacked Scull for paying him nothing and going on to make all this money. And hence the new era of art investment began.

One of the best bits was Hughes meeting Philippe de Montebello, Director for the last 31 years of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC. He was awesome, so dignified and articulate and not full of crap. He spoke of how museums stand no chance of buying paintings these days when pitted against the private collectors. Hughes asked whether, if the Mona Lisa was to do a tour of the world as it had in 1962 (I think it was), he would have it come to the Met. Montebello said a categorical no. He said he has held the Mona Lisa in his hands, out of its frame (!!), and that a painting like that is so transcendental you have a responsibility towards it. He said the Louvre have it in trust, for mankind, and that we are its guardians, not its owners, and must safeguard it. Hughes suggested it is at risk of conceptual degradation if it is reduced to celebrity status. Montebello agreed, it is possible to debase it. All v interesting. Art taken out of context, just based on money/celebrity, is at risk of losing its meaning.

And this was more or less how he finished up the show, saying that the risk is that if things continue going in their current fashion, then the old question of ‘what is the purpose of Art?’ will rear its head, and indeed what or where will the purpose be if its worth is solely based on its price and trendiness, rather than its importance or quality? His favourite, Rauschenberg, created works full of meaning and from meeting life head-on. Hirst, he claims, is an exercise in self-promotion and money-making.

I’m with Hughes on a lot of this. My knowledge of modern art is rubbish and I couldn’t really tell you which of the artists were the more important. But I’ve never really been able to view that diamond-encrusted skull as good art. I’m not saying it’s not art, just not good art – for me. And the whirl of money (apparently it’s the most lucrative unregulated market in the world after drugs) that surrounds does feel like it’s taking away rather than adding. In the most simple terms, people should buy a painting because they like it, not because it’s worth x amount of money. God I remember going to the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition once and seeing a bare canvas, about 75cm x 50cm, with a little painting of an apple somewhere near the bottom. It had a price tag for £6,000 or £8,000 (I forget which) on it. Unbelievable! The museum buyer guy said that a lot of good art never gets heard about because it’s not in a gallery/promoter’s interests to market it (it’s not of the moment etc.) – ie the marketing machine adds to the problem. But then again everyone needs marketing to some degree. Am still clarifying my thoughts on all this. (nb: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/sep/14/damienhirst.art for another point of view on Damien Hirst..)

So I wonder if there is a place for art now, revolutionary art? I don’t really know what I’m talking about to a point; I am someone who leans towards the traditional forms of art-making so maybe I’m unwittingly a bit old-fashioned. But there is so much media, imagery and information coming at us now; where does art sit in all this? A lot of it feels like it is art, meaningful or not, blasting away at us. So much information to take in. What could cut through it? Actually I have unintentionally said similar things to Robert Hughes again (!) – see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pMsQg3wuRvM where he talks about the distractions that surround a piece of art nowadays.

Hughes said that for him the best art is dense with meaning and confronts the question of why we are here (which I think is Damien Hirst’s goal often?). I like that and will think about it.”

sourced at http://kathrynpinker.com/2008/09/29/hello-world-2/