About David Hockney

(republished from brain-juice.com)

David Hockney has often been regarded as a playboy of the art world. He has had lascivious relationships, and he has run among strange and crazy artistic circles. Yet he has always retained a sense of stability in his life through his constant and tireless devotion to his work. Hockney is an artist that has always enjoyed success and praise, facing little to no hardship in his career. What is interesting about his life is not the problems he has encountered, but the strides he has taken to bypass much human suffering and malaise.

David Hockney was born on July 9, 1937, in Bradford, England, to Laura and Kenneth Hockney. The Hockneys were, as David said, a “‘radical working-class family.'” Laura and Kenneth were solid parents who only wanted their children to have the best education possible. Laura raised her children as strict Methodists and resolutely shunned smoking and drinking in the home. Kenneth was a passionate radical and a conscientious objector during World War I. David Hockney was always considered an eccentric in Bradford. He never really cared what people thought of him and always did as he pleased. He spent afternoons at Sunday School drawing cartoons of Jesus, much to his teachers’ dismay. As a young child, Hockney also developed an obsession with opera when he first saw the Carl Rosa opera company’s production of La Bohème.

In 1948, David Hockney won a scholarship to the Bradford Grammar School, one of the best schools in the country. Here he enjoyed his art classes most and thus decided that he wanted to become an artist. Furthermore, he disliked the other subjects he was required to study. In 1950, he asked to be transferred to the Regional College of Art in Bradford so that he could more seriously pursue his interest. However, the headmaster recommended that he first finish his general education before transferring anywhere. Hockney responded with misfit behavior towards his teachers and poor grades, even though he had found much success in school before this. He spent his class time doodling in notebooks. Nonetheless, his artistic leanings also won him prizes and recognition, and he drew comics for the school newspaper. Overall, he was a likeable and intelligent student with many friends.

In 1953, Hockney finally enrolled in the College of Art and began painting with oils, his medium of choice for most of his life. Hockney learned that painting was a process of seeing and thinking, rather than one of imitation. His artwork was abstract and quite personal and allowed him to deal with human sexuality and love in a public, yet still inhibited manner. He developed a penchant for painting mirrors and loved the artwork of painters such as Francis Bacon and other contemporaries. Socially, he made a lot of friends, but never really expressed any sexual interests. His group of acquaintances would often travel into London to catch various art shows. In the summer of 1957, Hockney took the National Diploma in Design Examination. He graduated with honors and then enrolled in the Painting School of the Royal College in London two years later, where and when he would gain national attention as an artist.

Hockney immediately felt at home at the Royal College. There were no steadfast rules or regulations. Not only did he find much success and pride in his work, but he also thrived in the many friendships he made there. He and his friends spent much of their time in the studio, but they explored the pubs and coffee bars around town as much as possible. Hockney was a serious student, however, and dedicated much effort to painting. During his first term, he experimented with more abstract styles, but he felt unsatisfied with that work, and he still sought his own style. His professors were good and receptive to his artwork, but Hockney seemed to learn the most from his fellow students who shared similar artistic interests and insights. Furthermore, he was quite a self-motivated sort of person and began to feel a need for meaningful subject matter, and so Hockney began painting works about vegetarianism and poetry he liked reading. After a little while, Hockney even began painting about his sexual orientation, writing words such as “queer” and ‘unorthodox lover” in some of his paintings. While Hockney had been aware of his attraction to males growing up in Bradford, he had never felt comfortable talking about his sexual orientation until he came to the Royal College and befriended other gay men.

In the summer of 1961, Hockney traveled to New York for the first time. His friend Mark Berger showed him around all the city’s galleries and museums, while his other friend Ferrill Amacker showed him the hot gay spots. To pay for the trip, Hockney sold several of his paintings. He was also able to work on other paintings and sketches while he was there at the Pratt Institute’s facilities. It was from his New York sketchbooks that Hockney came up with the idea for an updated version of William Hogarth’s “Rake’s Progress,” which he eventually finished two years later. Hockney was offered five thousand pounds for the plates and thus was able to live in America for a year at the end of 1963. In the mean time, he finished his studies at the Royal College and received considerable attention from critics, professors, and peers at several student shows. At this time early on in Hockney’s career, his artwork was poetic and tended to tell stories. He even wrote poetic ramblings on many of his paintings as well. For a short time, Hockney was in danger of not receiving his diploma because he had failed his Art History courses. Nonetheless, he was awarded the gold medal for outstanding distinction at the convocation and ended his college career on a tremendously good note.

In New York, Hockney befriended Andy Warhol, at whose studio young artists often met and socialized. He also met Dennis Hopper that same night. However, Hockney’s main purpose in returning to the States was not to meet peers, but rather to travel to California. Hockney had become fascinated with the images of young, built, and tan men in the publication Physique Pictorial, which he had collected while in London, and he was hungry to experience the sleazy underground world of Los Angeles. He immediately loved the city and made Santa Monica his home. Spending much of his day at Santa Monica pier, Hockney would just people-watch and admire the beautiful boys that seemed to be at the beach every day of the year. This new environment greatly inspired him. In his California paintings, such as Man in Shower in Beverly Hills (1964), Hockney featured mainly wet, sculpted men and typically colorful southern California architecture. Overall, he was enamoured of the more laid-back, sunny lifestyle that the city of Los Angeles provided. It was around this time that Hockney developed the naturalistic, realistic style he is most known for today.

In the summer of 1964, Hockney was invited to teach at the University of Iowa. He was generally bored with this new milieu but was able to complete four paintings in six weeks there. An old friend from London Ossie Clark came to America for the first time and visited Hockney in Iowa. The two traveled across the country a bit, visiting gay bars. At the same time, Hockney hosted his first American exhibition in New York. He received rave reviews and sold every painting.

In December of 1964, Hockney returned to London to give a talk on homosexual imagery in America. A year later, he returned to America to teach at the University of Colorado in Boulder. There he lived in an apartment without windows and painted the Rocky Mountains from his memory. After his term there, Hockney went to California with some old friends. One night in Hollywood, Hockney met the blond beach bum of his dreams, “a marvelous work of art, called Bob,” and took him home. The two drove to New York, and Hockney flew Bob out to London, but soon realized that it was a mistake and sent the boy home.

Two years later, Hockney experienced his first true romance with a nineteen-year-old student named Peter Schlesinger. Schlesinger was just about everything Hockney ever wanted in a man. He was attractive, smart, young, innocent, and in great need of Hockney’s guidance. Schlesinger became a favorite subject of Hockney’s, and the many drawings of him show the informal intimacy of the two. A year later, Schlesinger transferred to Los Angeles from Santa Cruz and moved into an apartment with Hockney. During the day, Hockney would paint, but at night the two would often lie in bed drinking wine and reading. Hockney was very happy. In June of 1967, Hockney took his new beau to Europe, and the two toured the continent. At this time, Hockney’s interest in photography grew. He would take endless shots of Schlesinger, mostly for fun, but also for study.

For many years after that, Hockney remained content painting and showcasing his work at various exhibits. His work had gained much esteem and attention all over the world. Critics instantly recognized the power of his art. Most of his paintings from the late sixties and early seventies, particularly Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy (1970-1971), adhered to the concept of naturalism — that is, representing things as they were actually seen. His interest in photography greatly advanced his skill in this area, but Hockney felt as though he depended on it too much from time to time. He liked using the photographs more for the study of light, rather than to aid his memory. For the most part, Hockney was concerned with finding a balance between pure skill and pure art in his idea of naturalism. He did want his art to seem overtly academic, but moreover, he had not satisfied his abstract tendencies.

In 1971, Hockney experienced some tension in his relationship with Schlesinger. The age difference had become a problem, and Schlesinger wanted some independence and room to grow. Hockney’s eye also began to wander, and his social life became more active once again. He continued to entertain large groups of people in his studio and basked in the glory of his fame. Hockney decided to travel to America for a break, and when he returned, he found out that Schlesinger had moved to Paris and had been having an affair. Although he was hurt, Hockney was very relieved. A while later, the two reunited in Barcelona, but once again had many difficulties. Schlesinger felt that Hockney placed his work above everything else and felt as though he himself were only an erotic object to be shown off to others. He decided never to move back in with Hockney again. Hockney was devastated and started taking Valium to combat the depression and loneliness he suffered.

In February of 1974, Jack Hazan finished a biographical film on Hockney’s life. At first, Hockney was shocked and devastated by the film, which had brought many issues that hit too close to home for him. In particular, he was disturbed by the film’s portrayal of his romantic relationship with Schlesinger. However, after the film had received some attention and praise, Hockney realized that he had to swallow his pride and sign for its release in order to give Hazan the respect and admiration he deserved. The film was banned in many countries for its explicit portrayal of homosexuality, but won many awards among the critics.

In the eighties, Hockney turned to photo collage. Using a Polaroid camera, Hockney would assemble collages of photos that he would take as quickly as possible. Hockney was fascinated with the idea of seeing things through a window frame. This medium allowed him to see things in a whole new fashion. He took a drive in the southwest United States taking thousands of photos and fitting them altogether into various collages, such as You make the picture, Zion Canyon, Utah. His artwork also began to take on a psychological dimension. In the autumn of 1983, Hockney began a series of self-portraits, allowing the public to enter his personal inner life. It is obvious in these works that Hockney was quite vulnerable and unsure of himself, even though he had achieved major success in his life as an artist.

In the nineties, Hockney continued to experiment with rising technologies. He used a color laser copier in some of his works and reproduced some of his paintings. Hockney was impressed with the vibrancy of color that could be achieved using such devices. He also began sending drawings to friends via fax machines and was thrilled with this new way of communication. Much of the appeal lay in the fact that these newly produced images had no financial value at all. Thus sharing art became a true act of love and appreciation.

Hockney’s life and all his loves are always on display to the public. By embracing all sorts of technology and media, Hockney has made his art accessible to people everywhere. He has used art to express the love he has felt for others, and consequently, his works show personal stake and personal meaning. Ironically, his artwork caused much personal suffering and strife in the making and breaking of his romances, while at the same time, garnering him much respect and admiration. Hockney has truly made art a form of real human interaction and communication.

David Hockney: not just bigger, but better

Hockney’s vast landscape Bigger Trees Near Warter – recently donated to the Tate – is a glorious work, not least because it’s so honest about the conditions of its creation.

“David Hockney is no fool. He understands art history – he has, after all, written books about it. For almost half a century he has succeeded in maintaining a place in the world of art, however unfashionable or odd the directions he happened to be taking. He’s pursued his own interests, and at the same time kept his art in the public eye. And in giving his painting Bigger Trees Near Warter to the Tate he executed a masterstroke. This painting, which has just gone on view for all to see at Tate Britain, will do his reputation wonders as the century progresses. It is a triumph.

You thought Hockney was old hat? We all get it wrong. Art is beautiful because it makes fools of us. You can set up any ideology you like, define taste by any criteria you choose, and a work of art will come along to stand your prejudice on its head. If you prove by logic and erudition that art cannot come readymade, some young philosophe will display the most incredible found object that was ever put in a vitrine. This is what happened to critics 20 years ago. Nowadays, the prejudices are reversed – and so are the surprises. As the artistic ideas of the 1990s gradually sputter out, the life comes from elsewhere. From Bridlington, in this case.

I’ve seen Hockney’s studio there, and it’s just a room in his house, with a view over the town. It’s bizarre to think of him creating the vast Bigger Trees Near Warter in this little working space. But of course, he also has spacious facilities in Los Angeles. Did he make this picture piece by piece in Yorkshire, or finish it in LA? I don’t know. It’s just one of the musings that occur to you when you are surrounded by painted trees glowing in a perfumed light. Pinks and purples, a world under the sky – a largeness that caresses.

Hockney believes that painting must renew itself by confronting nature. It is about hand, eye, brain and heart. You look, you feel, you sketch. Putting his easel in the open air like a 19th-century French landscape artist, he has set out to paint in a pure and honest way. And as you contemplate one of the best pictures he has ever made, you’ve got admit he has a point”.

sourced @ http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2009/oct/28/david-hockney-tate-bigger-trees

There’s a courage to David Hockney’s Yorkshire landscapes

“The tradition of open-air painting celebrated in the National Gallery’s Corot to Monet show is still alive in the hands of David Hockney”.

Aglow with emotional light …

Aglow with emotional light …

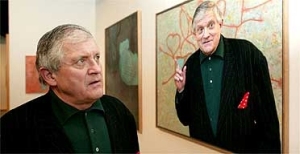

David Hockney stands in front of Bigger Trees near Warter (2007), his gift to Tate Britain.

Photograph: Heathcliff O’Malley/Rex Features

“You’d have to have a heart of stone if you weren’t moved, just a little bit, by the prospect of an elderly painter standing in a wide open east Yorkshire landscape, touching clouds and sky and trees into a second existence on a canvas that is blowing in the wind. It’s a scene that has stayed with me from Bruno Wollheim’s recent film about David Hockney for the BBC’s Imagine series.

I found myself thinking about the film, which showed last week, when I went to see the fantastically intelligent new exhibition Corot to Monet at the National Gallery the other day. This sensitive (and free) survey of French landscape art in the decades before impressionism begins with a room full of open-air paintings, by artists who made the pilgrimage to Italy in the 18th century. It’s not confined to French painters but also includes Thomas Jones’s A Wall in Naples; it seems the light and space of Italy inspired artists very early on to get out of their workshops and mount their canvases in the open.

Wollheim’s Imagine film shows Hockney continuing this tradition. He drives around the east Yorkshire landscape, finds a spot, and starts painting by the side of the road. There’s something very magical in the sequences that capture the fragility and vulnerability of the canvas mounted in the open air.

Hockney’s experiment is courageous. I don’t think all his Yorkshire paintings come off, and a lot of them together make me want to go and see a video installation, quick. But then the seriousness and honesty of them hits you, and you start to look closer. The fact is that when it works – when the light is right and his eye is right – he has produced some enduring landscapes. Remote from fashion, apparently remote from his own history, they glow with an emotional light. Wollheim’s film does a real service by recording how they were made”.

sourced @ http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2009/jul/07/david-hockney-art-landscapes

Do we really live in a non-visual age?

“David Hockney claims we don’t look at the world any more, but with so many images bombarded at us, you could say we see too much”.

“

Do we live in a non-visual age? This is the latest claim by David Hockney, who in recent years has proved he can make headlines as a cultural commentator as well as an artist. His polemical views have included saying that western art is deeply involved with the lens – the thesis of his book Secret Knowledge – and, in apparent contradiction, arguing that photography is dying out.

Hockney’s latest claim is that we don’t known how to look any more, or enjoy looking. “I think we’re not in a very visual age. You notice that on the buses. They don’t look out of the window. People plug in their ears and don’t look much… It’s producing badly dressed people…”

At first sight this might seem an absurd claim. We live in a world saturated with visual stimulants. Surely the entire point of pop art, the movement to which Hockney belonged in the 1960s, is that adverts, films and what Warhol called “all the great modern things” dazzle us, and visual overload has increased massively since then.

What then is he talking about? You have to consider the context of his comments – made at the launch of the Turner exhibition he curated at Tate Britain. And when you look at Turner’s watercolours – or for that matter at the art of Constable, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Dürer or Titian – you have to wonder why these artists saw the world so intensely. Why does Constable have so much time to look at a tree? Why can Rembrandt see so deep into a face?

There really is evidence, in great art, that people in earlier times could have richer visual experiences than modern inhabitants of consumer societies. Yet surely, if this is true, it has more to do with the proliferation of the visual than its eclipse. In a world with less to look at, people spent more time looking at simple things. You can’t be Vermeer today because, rather than spend all morning watching someone working in the kitchen, you’d be distracted by the TV or internet. So in fact, we look at too many things, and don’t look for long enough.

But there I go, falling into the same trap that has snared Hockney and so many intellectuals. His speculations remind me of the French theorist Michel Foucault whose overarching theses – that sex didn’t exist before Victorian times, madness is a modern invention and prison the template of modernism – are terrifically interesting but don’t recognise the complexity of life.

In fact you can say we don’t look, or that we look too much, and find evidence for both propositions. The reality is infinitely difficult to capture and impossible to theorise. Empiricism is better because it reminds you to learn from experience, and beware of generalities. Or to put it another way, it’s not wise to judge people from how they behave on the bus.”

Sourced @ http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2007/jun/12/havewelostsightofthevisual

Hockney Selects Watercolours

“Still controversial at 70, David Hockney yesterday spoke of his fears that Britain was moving into a post-visual age, where people no longer really look at things, and instead wander round plugged into MP3 players. “It produces a lot of badly dressed people,” he insisted. For the record, the artist was in black trousers and polished shoes, pale blue polo shirt, grey jacket, bright green polka dot braces, black and white spotty hanky, and white linen flat cap.

“My eyes are the greatest source of pleasure to me,” he said – and for anyone with eyes to see his selection of Turner’s watercolours, pictured left, can only give pleasure.

“You can see him working,” Hockney said of the dazzles of light and colour he chose. “You can see his hand moving, his eye, his heart moving his hand. Well worth looking at for anyone who is interested in the visual.”

Hockney’s selections were drawn from thousands of Turner watercolours in the Tate collection, left to the nation after the artist’s death. They are part of the largest selection of watercolours the gallery has ever hung, filling the Turner galleries while many of the big oil paintings which came in the same bequest are on tour in the US.

Hockney himself is contributing an enormous 50-canvas piece to this year’s summer exhibition at the Royal Academy, and more large new works, all painted in woodland near his Yorkshire home, are hung in the Tate Britain stairwell.”

Hockney on Turner Watercolours:

sourced @ http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2007/jun/12/artnews.art

Disposable cameras

We can’t trust photographs. In fact, we never could. In an exclusive interview, David Hockney tells Jonathan Jones why painting creates a more reliable record of the truth

“Do you know what Edvard Munch said about photography?” David Hockney asks me. “He said photography can never depict heaven or hell.” We’re talking about Hell at the Fine Art and Antiques Fair in London’s Olympia. Hockney recently drove to Spain from his current home in west London – “Those autoroutes are empty. It’s fabulous, like driving in Arizona” – and saw Goya’s Third of May in the Prado. He noticed that Goya had painted this horrific scene of a mass execution in Madrid in 1808 from a viewpoint no photograph could have achieved.

It adds fuel to his belief that painting can do things photography can’t, even when it comes to telling the truth about war. Everyone used to assume photographs of war were “true” in a way photography can’t be. But Hockney argues that the digital age has made such a conception of photography obsolete. You can change any image now in any way you want. He once saw what a famous LA photographer’s portrait of Elton John looked like before it was retouched. The difference, he says, was “hilarious”. And now everyone can do this.

“My sister, who is just a bit older than me, she’s a retired district nurse, she’s just gone mad with the digital camera and computer – move anything about; she doesn’t worry about whether it’s authentic or stuff like that – she’s just making pictures.”

If photography is no longer blunt fact, why not accept that painting has equal status? War photography is as fictional as painting, but painting can express profound insights denied photography. The famous photograph of a Russian soldier placing the red flag over Berlin is an example: “With the man putting the flag on top of the Reichstag – how did the photographer happen to get there first?” wonders Hockney. By contrast, Goya’s image of the executions of May 3 1808 has a truth that transcends whether or not he was an eyewitness. Hockney thinks Picasso, when he painted his extremely anti-naturalist Massacres in Korea in the 1950s, was making this very argument against photography: instead of random glimpses of violence, Picasso’s painting presents his understanding of the war.

It’s funny, talking about war and politics with David Hockney. Gloom and doom was why he left first Bradford, then Britain. “I grew up in austerity in the 1940s and 1950s. You didn’t know at the time, of course – you didn’t know any different.”

Hockney talks about his father, in the Bradford accent that has never deserted him after decades of living in Los Angeles and now London. “He was a very eccentric man. He was constantly writing to Stalin – every week. He used to tell us how important these letters were. We didn’t think so. We didn’t think Stalin would be waiting for them.” What were the letters about? “Peace, war. I’ve given up on all that, I think. I think the Enlightenment is leading us into a dark hole, really. Goya saw that. A lot of people, given the chance, would blow up everything, and you and me.”

We’re talking about Goya’s visions of hell, but I’m thinking about a vision of heaven: David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash, painted in 1967. In it, the sky is different from the water only in that it is a paler shade of blue. Between the luxuriant nothingness of the pool and the empty, warm sky is a low pink house with a reflecting glass wall, a canvas chair and two palm trees. In the foreground is a yellow diving board, and beyond it, the only motion in this eternally afternoon world, are explosions and curlicues, the aftertrace of a diver.

Hell is not Hockney’s subject. Paradise is what his eye has pursued. “I always wanted to be an artist because I like looking – scopophilia, is it called?” he says.

In the 1960s, Hockney did as much as the Beatles to end the British culture of austerity he grew up with, to assert that pleasure matters. The postwar painters were severe chroniclers of ration-book misery. We’re here at Olympia to celebrate one of them: Prunella Clough, whose first retrospective since her death in 1999 includes her 1950s realist portraits of workers as well as her later, more playful and sometimes gently lovely abstractions. “It’s very good that you’re doing this,” Hockney tells the exhibition’s curator, Angus Stewart, who says Clough was suspicious of people who lived too comfortably. Hockney says that’s typical of a lot of British people. “But I’m not like that.”

He also remembers, among the leading painters when he came to London, the Scottish duo Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, who “always wore these shiny suits – never wore anything else. They were shiny from never having been off – that kind of shiny.” David Hockney wore a shiny jacket to graduate from the Royal College of Art – but this was the other kind of shiny: superstar shiny. It was made out of gold lamé.

Hockney is so famous, so popular, such a great talker and character that it’s easy to take him for granted as an artist. If you’re a critic, it’s tempting to give him a bash. But Hockney is a significant modern painter. He is one of only a handful of 20th-century British artists who added anything to the image bank of the world’s imagination. Francis Bacon’s screaming popes, Richard Hamilton’s Mick Jagger and Damien Hirst’s shark are icons of irony, and grimly Hogarthian. Hockney is something very different, a modern Gainsborough, whose eye is entranced by beauty. This is a very radical thing to be.

He was by far the most hedonist of the 1960s pop artists, the only painter who put sex and utopianism at the heart of his decade. He was British art’s first pop star. But this was not because he made easy images. His paintings unequivocally praised gay sex – for example, Two Men in a Shower (1963). They were so innocent they disarmed everyone.

Hockney’s utopia was America. “I went to New York in the summer of 1961. I thought this is the place, this is it. It ran 24 hours a day for everybody. Here in London everything closed early. I used to complain about that like mad. I don’t care now – I go to bed at 11.” In his 1961-3 series of prints A Rake’s Progress, “The 7-Stone Weakling in America” for the first time visits gay bars until “The Wallet Begins to Empty”.

American freedom entranced him a lot more than Swinging London. “Girls in small skirts, it’s OK. You know I’m not that bothered about them. I preferred the white socks in California, actually. I did.”

Hockney now berates photography and yet, famously, a lot of his art has been made with photography. Like his friend Andy Warhol, he was interested in the world you see through the lens. His series of images of the pursuit and loss of heaven on earth – the swimming pools, Beverly Hills Housewife (1966), Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970-1) – are paintings that superficially resemble photographs.

When I look at A Bigger Splash again, I am surprised how much the quotation he dropped on me from the symbolist painter Edvard Munch applies to his own work. Hockney doesn’t paint hell, but the heaven on earth, at once blissful and unattainable, that he found in California and mourned in the aftermath of the 1960s is a vision photography could never quite create. A Bigger Splash is a painting about an inner state, an emotional state, somewhere between intoxication and death – it is the perfect invocation of a beauty so powerful it hits you like a wall, so empty it has no solid lines. Blue, pink, white.

Hockney says beauty is the thing none of us can resist. He saw a picture of a Colorado University football player accused of rape and the man’s face was so incredibly beautiful, he found it impossible to believe he was guilty. “Human beings always recognise a very beautiful creature, and open the door for them.”

The libertarianism of the 1960s is still there in Hockney, and still challenging. When the Guardian commissioned and printed Gillian Wearing’s Cilla Black on the cover of G2 last year, which carried the words “Fuck Cilla Black”, he “thought it was quite funny. I had no idea Cilla Black was alive or anything.” He was amazed that so many letters attacked it. The paper’s art critic defended this as a work of art. Fine. Then Hockney read an interview in the Guardian with a man who spent two years in prison for downloading images from the internet. The man claimed he did not think the pictures were wrong, but innocent and beautiful. “This man who, from human curiosity, looking for innocence and beauty, gets some pictures from the internet and does two years in prison for that. Why don’t you art critics talk about that?”

This is why he wants to get people thinking about photography – the way we see, and the power of images. “It’s time to debate images, especially when someone’s going to prison for downloading them.”

Photography, with its claim to truth, is a discipline, he thinks, and he’s glad digital technology is ending the rule of the one-eyed monster that never lied. “I suppose I never thought the world looked like photographs, really. A lot of people think it does but it’s just one little way of seeing it. All religions are about social control. The church, when it had social control, commissioned paintings, which were made using lenses” – as Hockney has argued in his book Secret Knowledge – “and when it stopped commissioning images, its power declined, slowly. Social control today is in the media – and based on photography. The continuum is the mirrors and lenses.”

Hockney is an artist who, at his best, broke free of all disciplines, of photography or politics or anything else, to paint his own paradise. He’s still looking for enjoyment. He left America because it has become so prissy about smoking and drinking – but he’ll go back, he says. He smokes with evident pleasure. “I was born in Bradford in 1937, it was the smokiest place on earth. We all survived – some people might have coughed a bit and fallen over.”

Having been so long in America, there’s a lot of Europe he hasn’t seen. He’s just been to Andalusia for the first time. The Spanish, he says – they know how to enjoy themselves.”

sourced @ http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2004/mar/04/photography